Will Australians need vaccine ID to do fun things?

Contributors are not employed, compensated or governed by TDM, opinions and statements are from the contributor directly

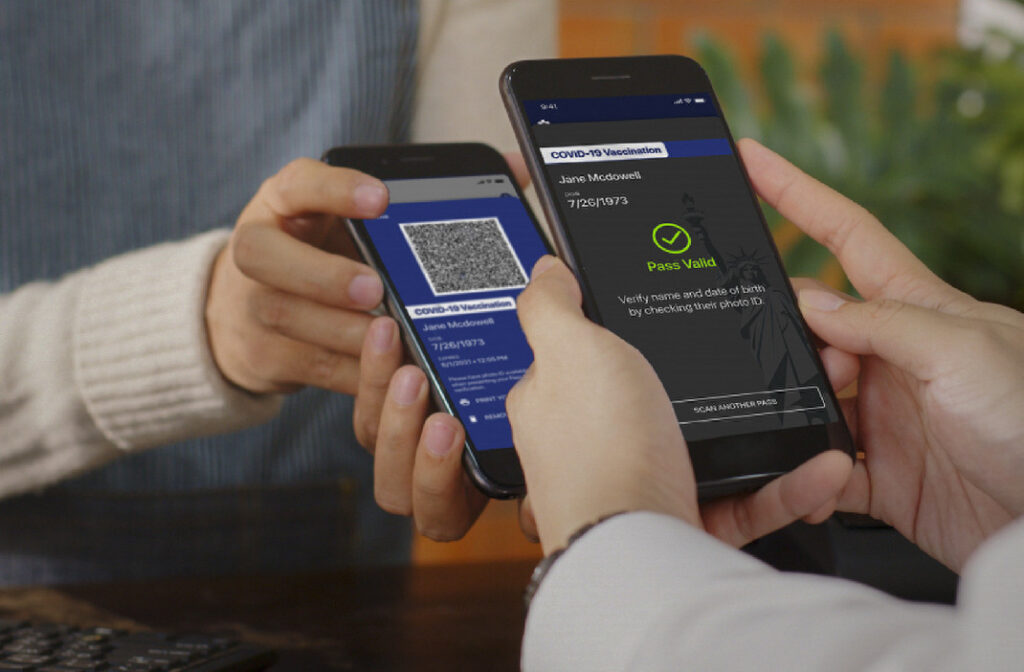

The Federal Government announces two weeks ago that the Covid Pass app could be available by November this year, however, are Australians ready to show vaccine ID if they want to go out on the town when summer begins? It has not been announced yet if we might have to show our COVID vaccination record to get into restaurants, bars, nightclubs, and outdoor music festivals.

In the U.S. and some countries in Europe after resisting the divisive concept of vaccine passports through most of the pandemic, a fast-growing number of private venues and some local officials are now requiring proof of immunization in public settings to reduce the spread of the highly transmissible delta variant of the coronavirus.

It may be unlikely that Australia will adopt a national mandate like the one in France, which on last Monday began requiring people to show a QR code proving they have a special virus pass before they can enjoy restaurants and cafes or travel across the country, however, the last call lies with the states and territories.

There is scope for Australian governments to impose a similar “vaccine passport”.

It’s important to bear in mind this kind of mandate is very different from forced vaccination (where an individual is forcibly inoculated). Rather, mandates create a set of negative consequences in cases of non-compliance.

The most obvious example in Australia is the “No Jab No Play” policies that restrict access to childcare in most states for children who are not fully immunised.

In the same vein, COVID-19 vaccination could be made mandatory for specific purposes, such as access to certain public or private spaces, travel, or certain types of employment, such as the pending vaccine requirement for aged-care workers.

From a legal perspective, the key limitation for government mandates pertains to discrimination.

The mandate must not discriminate, and therefore exemptions must be available for those who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons.

There is no protection under Australian law, however, for “discrimination” against people who are opposed to vaccination because of their personal beliefs.

Countries like France and Italy have dealt with vaccine refusal by enabling people to show proof of a recent negative COVID test as an “opt-out” measure to the vaccine mandate.

This is good behavioural science since it makes the option available – albeit more burdensome than the default of vaccination.

Private sector vaccine mandates are also feasible in Australia for COVID-19 and other diseases. These mandates can apply to workers, clients, or both, provided they align with existing employment and consumer laws.

Unlike in the US, where many major companies are mandating COVID vaccines for employees, the measure is still framed in Australia as a possible exception to the general rule.

However, this could become more widespread in Australia after the Fair Work Commission ruled in several cases this year that it was reasonable for employers in the aged care and childcare sectors to insist on flu vaccinations for staff.

Mandates may be easier to establish and implement in the private sector because companies are generally subject to less scrutiny and accountability than governments.

They can also rely on arguments about their duty of care to workers and clients.

Government vaccine mandates must be linked to other conditions for which governments are responsible and accountable, such as the available supply of vaccines.

A broad-based government mandate in the absence of adequate supply could be subject to court challenge and risk being political suicide.

By contrast, private entities do not share the same level of responsibility for providing vaccines when enacting such mandates on clients. In the case of vaccine mandates for employees, however, the duty to provide vaccines is much higher.

Would Australians support vaccine mandates?

Research shows Australians are broadly supportive of vaccine mandates, and they prefer vaccine passports to other kinds of mandates.

However, the high levels of support for government mandates may not be the same now, given public perceptions of the government’s vaccine rollout failure.

Australians may be less trusting of the government and, therefore, less supportive of government-mandated vaccinations.

This demonstrates that the obstacles to the introduction of vaccine passports are not only legal but highly political.

Mandates can be good public policy when they are appropriately designed and defensible from ethical and epidemiological perspectives. These attributes are largely within government control.

However, when governments do not take sufficient action to address hesitancy in the community, this can create the conditions that make mandates appear attractive or necessary.

Comments are closed.